Day 1 – Chords in the major scale

After we laid down the basics yesterday in Day 0, let’s tackle the chords of the major scale and the idea of “key” today.

Check out the complementary (and complimentary) video lesson at the bottom too.

Let’s go!

1. Basic chords

Chords are groups of notes sounding together at the same time. They’re like grapes to melodies’ breadcrumb trails.

The most basic chord in popular music is the power chord. It is made up of two notes a fifth apart, for example C and G or G and D.

The lower note is the root of the chord and gives it its name. C and G form the C power chord (also written C5). G and D form the G power chord (G5).

The higher note is the fifth (read “the 5th degree of the 7-note scale built on the root of the chord, which is also a fifth above that root”).

The second most basic chord is the triad. It is made up of three notes — the root, the fifth and the third, which as you might have guessed is the 3rd degree of the 7-note scale built on the root of the chord, which is a third above that root.

Where the fifth gives a chord its power (it is the first harmonic of a note after the octave), the third gives the chord its colour.

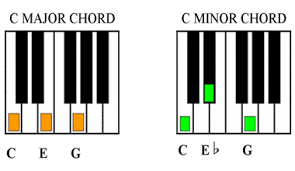

A triad is a major triad when it contains a major third interval (4 semitones) between the root and the third of the chord and a perfect fifth (7 semitones) between the root and the fifth.

A triad is a minor triad when it contains a minor third (3 semitones) between the root and the third of the chord and a perfect fifth (7 semitones) between the root and the fifth.

Before it gets any more confusing, here’s an example:

From the C major scale we take the 1st, 3rd and 5th degree to build a triad like this:

C D E F G A B C D E F …

C . E . G . .

It’s a major triad since C–E is a major third. It’s the C major chord. We write it as Cmaj or simply C.

Now, let’s do the same but starting to count from D, like this:

C D E F G A B C D E F…

. D . F . A .

This is a minor triad since D–F is a minor third. It’s the D minor chord. We write it as Dmin or Dm.

The we start from E and we get E minor:

C D E F G A B C D E F…

. . E . G . B .

What do you think will happen if we kept going up the scale this way?

2. The major key

We’ll get 7 chords — 7 triads — all of which use the 7 notes of one and the same scale — C major. When in a song you use only (some of) these chords, we say that the song is in the tonality or the key of C major.

And the 7 chords of this key — the 7 diatonic chords of the C major key — are:

C major, D minor, E minor, F major, G major, A minor and B diminished.

The only chord different from the major and minor triads we saw above is the diminished chord built on the 7th degree of the scale which contains a minor third between B and D (the root and the third of the chord) but also, significantly, a diminished fifth (6 semitones) between B and F (the root and the fifth of the chord).

To sum up, we get major chords on the 1st, 4th and 5th degree of the scale (C, F and G); minor chords on the 2nd, 3rd and 6th degree (Dm, Em and Am);

and a diminished chord on the 7th degree (Bdim).

Whichever way you put these chords together, you’ll be playing in the key of C major.

And you don’t need more than the chords in one key to write a song like Adele’s “Someone like you”.

In fact, you don’t need more than 3 chords either — just look at “La Bamba”.

At this point, you know enough to do today’s challenge and you can skip ahead if you like.

But if don’t want to miss the really interesting part, keep reading.

3. Chord functions in a key

Not all chords in a key were created equal.

Some are stable and some — less so.

The strongest, most stable chord is the one built on the 1st degree of the scale — the tonic. As the “founder” of the key (tonality), to which it has given its name, this chord is its natural boss, base camp, home base and home run.

It is the chord any song would like to rest on. Unless, like me, you like to tease.

The chord that has the strongest pull towards the tonic (and possibly the biggest tease), and which often precedes it in the chord progression, is the one built on the 5th degree of the scale — the dominant. It is at once the closest relative and the strongest opposite to the tonic and they just have to be together. You know how it is with siblings or couples.

The 5th degree is the other note in the power chord built on the 1st degree. It is also the strongest overtone contained in that first-degree note (after the octave). And on top of that, the dominant chord contains the leading tone — the 7th degree of the major scale — which is just a semitone below the 1st degree and thus has a very strong pull towards it too.

In C major, the dominant chord is G major, whose 3rd degree is B — the leading tone in the scale.

You have to hear it to believe it.

The third most important chord in the key is the one built on the 4th degree — the subdominant. Like the first two, it is a major chord and you can think about it as a stepping stone towards the dominant or else as a calmer, less tense counterpart, because its root is a fifth below the root of the tonic and its fifth is the root of the tonic.

In C major, the subdominant chord is F major — F-A-C.

Between them, the tonic, dominant and subdominant contain all the notes of the major scale.

And the two most common cadences (chord sequences at the end of a piece) in Western music are the V -> I and IV -> I cadences.

4. Roman numerals

Wait, what?

OK, this is the last bit of mind-blowing info for today 🙂

One common use of Roman numerals in a musical context (I believe in Nashville they use Arabic numerals to a similar effect) is to represent the degrees in a key that chords are built on.

Upper case Roman numerals denote a major chord; lower case numerals — a minor chord.

In the example above, V -> I and IV -> I denote going from the dominant or the subdominant to the tonic.

In C major, those progressions are G -> C and F -> C.

But in F major, they would be C -> F and Bb -> F, because in that key F major is the tonic, Bb major is the subdominant and the dominant is C major.

So when you see something like

vi ii V I or I vi IV V

you’ll know (with practice) which chords to use from the key you have chosen and furthermore you’ll know how to transcribe any chord progression to the key that best suits your voice or the key that the band leader commands.

In the key of C major, the above progressions are:

Am Dm G C and C Am F G

And the 7 chords in a major key look like this:

I ii iii IV V vi vii°

5. Today’s challenge

Assimilating all the above if you haven’t heard it before is a challenge in itself, but since we’re here to practice, here are a few hands-on assignments (if you’re short on time, stick to the first):

- write out 3 chord progressions using only chords from one key

- write them out in Roman numerals

- transpose them to at least one other major key (after C major you can try G, then D, A and E, or F, then Bb, Eb and Ab).

Have fun and don’t hesitate to share your work or ask questions in the comments below.

See ya tomorrow for Day 2 – Melodies.

Almost forgot — today’s video: