Day 1 – Seventh chords

Welcome to the chords songwriting challenge!

If you find this Day 1 too steep, feel free to revisit Day 1 of the Basic Theory Challenge or even do the whole challenge from the start.

If you’re iffy about black characters on a screen, meet my lovely teaching persona in the video below.

And don’t forget this is a practical charade. Challenges are at the bottom (which is where you start to get to the top) and if you need help – holler!

Right, enough precautions. Let’s dive in.

Today, we start with seventh chords, which are 4-note chords using the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th degree of a scale.

I chose to start with seventh chords because of the single most important chord you’ll learn this week (if you don’t know it already) — the dominant seventh chord or the V7 chord — built on the 5th degree of the major scale.

This chord is the major vehicle of harmonic movement in (Western) music because it combines the forces of diatonicism and chromaticism and can single-handedly spice up your chord progressions beyond recognition.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s do a quick recap of the basic chords in a major key.

1. Diatonic triads of the major scale

You might remember when we looked at the major scale, that we can take the 1st, 3rd and 5th note, counting form each of the degrees of the scale to form 7 triads — the diatonic chords of the major scale.

In C major (C D E F G A B C D E F…), those are C major (C E G), D minor (D F A), E minor (E G B), F major (F A C), G major (G B D), A minor (A C E), B diminished (B D F).

Written out in Roman numerals, these are:

I ii iii IV V vi vii°

Whatever note we build the major scale on, we get major chords on the 1st, 4th and 5th degree, minor chords on the 2nd, 3rd and 6th degree, and a diminished chord on the 7th degree.

The I chord is the tonic chord — the key center, the home base, the final resting place. The V chord is the dominant chord — the natural predecessor of the tonic, which seeks to resolve to it. And the IV chord is the subdominant chord — often preceding the dominant, possibly balancing it out (it is a fifth below the tonic, as the dominant is a fifth above it).

These three triads contain all the notes of the major scale and are the only chords used in countless simple songs.

Not surprisingly, the most common cadences (chord sequences at the end of a progression) in Western music are V -> I (perfect cadence) and IV -> I (plagal cadence).

2. Diatonic seventh chords of the major scale

The I, IV and V triads are all major triads, but their functional difference really becomes apparent when we build 7th chords instead of triads.

As above, we start counting from each degree of the scale, but we take the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th note.

In C major, that gives us two major seventh chords on degrees 1 and 4 — Cmaj7 (C E G B) and Fmaj7 (F A C E) — in which there is a major triad and a major seventh interval (11 half-steps — just a semitone short of an octave) between the root and the seventh of the chord.

There are also three minor seventh chords on degrees 2, 3 and 6 — Dmin7 or Dm7 (D F A C), Em7 (E G B D) and Am7 (A C E G) — in which there is a minor triad and a minor seventh interval (10 half-steps — a whole tone short of an octave) between the root and the seventh of the chord.

There is a half-diminished chord on degree 7 — Bm7/b5 or B⌀7 (B D F A) — which contains a diminished triad with a minor seventh interval. (We’ll look at the diminished 7th chord, in which the fourth note is a major sixth from the root, in Day 4.)

And finally, on degree 5 we get a dominant seventh chord — G7 (G B D F). It combines a major triad with a minor seventh interval between the root and the seventh of the chord (a major with a flat 7th).

One reason this chord is special is because its root is a perfect fifth above the root of the tonic chord and thus it is already contained in the tonic (power) chord. The root of the dominant seventh chord is also contained as a prominent overtone in the harmonic series of the root of the tonic. There are fun scientific reasons for this, but if you prefer not to rekindle painful memories about physics in school, let’s just say that roots like to move in fifths.

The other reason this chord is special is that there are two leading notes (aka leading tones) in it.

Usually, we refer to the 7th degree of the major scale (B in the scale of C major) as the leading note because it is just half a step below the tonic and pulls towards it.

In more general terms (especially in the context of voice leading, which we’ll talk about later this week), a leading note is any note in a chord which moves by a semitone to a note in the next chord.

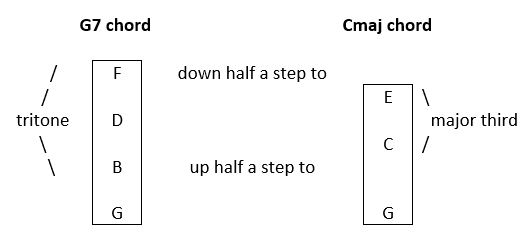

The G7 chord contains 2 leading notes: B which pulls towards C, and F which pulls towards E.

Importantly, the interval between these two leading notes — a tritone (6 half-steps) — is also very unstable, which is yet another reason for the dominant seventh chord to carry so much tension that wants to be resolved.

(The tritone is exactly half an octave (= diminished fifth = augmented fourth) and was apparently so dissonant to the Medieval church that it forbade using it.)

In the case of the perfect cadence (V -> I), the tritone can resolve inwards to a major third or outwards to a minor sixth:

In this example, the C major chord is in 2nd inversion (more about chord inversions in Day 5) and we have perfect voice leading in which one note remains the same (G) and two others (B and F) move by half a step to a note in the next chord.

So, to sum up, in Roman numerals the seventh chords of the major scale look like this:

Imaj7 ii7 iii7 IVmaj7 V7 vi7 vii⌀7

3. Chord substitutions

Now that you know about seventh chords, you can take any old chord sequence and make it new by replacing one or more of the triads in it by a seventh chord.

(Hint: try a V7 chord for a V chord first)

For example: Am Dm G C could become Am Dm7 G7 C.

In the key of G major, that would be Em Am D G and it could become Em7 Am7 D7 Gmaj7.

And so on.

4. Chord substitutions — triads in seventh chords

Now if you take the chord of Am7 (A C E G), you’ll notice that it actually consists of two triads — A minor (A C E) and C major (C E G).

It is not unthinkable then to substitute Am for C and vice versa.

In fact, the scale of A natural minor uses the same notes as C major, which is why the two keys are called relative keys. A minor is the relative minor of C major and C major is the relative major of A minor.

The same is true about D minor and F major and E minor and G major — all of them are triads in the key of C major and in each case you can substitute one for the other.

Of course the minor chords will give you a more somber feel and the major chords — a brighter sound. It’s up to you to decide what you need for your song exactly.

If you want to take this a step further, you’ll notice that the A minor triad is also part of the Fmaj7 chord, just as the E minor triad figures in Cmaj7, so it is possible to replace F by Am or C by Em. This substitution is trickier though and will change the sound of your progression even more. Still, it’s worth experimenting with.

On a final note, B diminished is a good substitute for G or G7 and is said to have a pronounced dominant function, because as we have seen above, it contains two leading notes and an unstable tritone interval that guarantees a strong resolution to the tonic chord of C major.

So, Am Dm G C from the example above could become C Dm Em C, or C F Bdim Am, or Am Bdim Em Am, etc.

5. Today’s challenge

We’re not back to school and this is not an assignment.

It’s a real challenge, given all the rest you have to do in your life.

If it doesn’t kill you, it will only make you stronger!

So, each day you are to try and create a new song (fragment) or more using what we’ve talked about on the day.

The idea is to breathe sound into the theory so that it materializes in your mind and opens up new pathways in your practice.

Ideally, you would share what you come up with in the comments below (with or without sound) and since we’re all here to learn (including me) and have fun with friendly like-minded people (I’m counting on you), there are no wrong ideas.

(Yes, all comments and ideas are right! They are also welcome, awesome and extra cool! AND you get bonus points for them in my secret book. )

So let’s start with a common chord progression today. One of yours or one of your favourites. Take it and make a few substitutions in it by using one or more of the following:

- a seventh chord (instead of a triad with the same root)

- a relative major or minor triad

- a related triad

(More) Bonus points for trying out a new key like G major or F major.

What about a minor key, you say? Yes, of chords! We’ll talk about it tomorrow.

And, before I forget, here’s today’s video illustration, as promised:

OK so I chose the 50s progression C – Am – F – G

Quite enjoyable was this variation:

C – Am – Fmaj7 – G

also not bad was

Cmaj7 – Am – F – Bm flat5

That’s great Kath!

As a next step, you could try transposing the variations to a different key, or stringing different variations together…

Enjoy!

Hi, I tried to tweak the Andalucian cadence and it worked nicely.

Am7, (ACEG) G, F7 (FACE), E

Hi Kauko,

That’s great!

By F7 I presume you mean FACEb, because FACE would be Fmaj7.

This last one would actually work nice if you replace the G by a G6 chord (GBDE), because you’ll have an E in all chords which can be a pedal note in the bass or in the melody 🙂

You’re welcome to include a link to your song if you like!

Cheers,